Notes on Atoms for Peace and War

By Dr. Nick Touran, Ph.D., P.E., 2019-12-07, Reading time: 35 minutes

The freely downloadable book, Atoms for Peace and War By Richard Hewlett and Jack Holl is an official Atomic Energy Commission history covering the Eisenhower years from 1953 to 1961. It explains the early efforts to build up an economical peaceful nuclear industry and shows how these efforts coincided with an increasing public understanding of the dangers of fallout from nuclear weapons. A long read (733 pages), this is something that any serious student of nuclear history will find fascinating.

This page is a collection of some notes I took while reading, augmented with a few relevant links. I read it primarily from the perspective of understanding the development of commercial nuclear reactors and took more notes on topics relevant to this interest.

The First few Chapters

Eisenhower was elected on November 4, 1952. He was elected only 72 hours after the US successfully detonated the world’s first thermonuclear weapon, Ivy Mike. Thus, the Eisenhower administration and the possibility of thermonuclear war were born almost simultaneously. The book opens as president-elect Eisenhower is briefed on thermonuclear weapons on November 11. From the beginning, the utterly devastating potential destruction of such weapons motivated Eisenhower to direct the world in a peaceful direction. The stakes of peace were now higher than ever.

Eisenhower also heard in this briefing that the first generation of electricity had occurred in the Experimental Breeder Reactor-I in 1951, that a land-based prototype of a nuclear-powered submarine was nearing completion at the national reactor testing station in Idaho, and that nuclear-powered aircraft were under development at the Oak Ridge National Lab. Four joint ventures between industrial teams and the AEC had been proposed to develop commercial nuclear power plants. The AEC was trying to figure out how to release commercial nuclear technology without giving certain private companies undue advantages over others in the free market.

Eisenhower was the first Republican president in 20 years, and he was determined to find ways to kick-start commercial nuclear power in a way that would bolster private industry and reduce the concentration of power and knowledge in the federal government.

Economic nuclear power was thought promising, but known to be far off. Submarine power would be the first large-scale use, since the capabilities of nuclear power underwater have no competition. Finding ways to make nuclear power competitive with conventional power plants became a primary focus. The Joint Committee on Atomic Energy was also keenly interested in this, and in 1952 compiled a 400-page volume of information, Atomic Power and Private Enterprise. At the time, it was thought that one way to get private industry involved would be to make “dual-purpose” reactors that made heat/electricity for utility purposes and could sell Plutonium byproducts to the AEC for use in weapons. (This dual-purpose idea was soon thereafter dismissed because the production reactors at Hanford and Savannah River made sufficient quantities).

Sidenote, another few hundred pages of testimony from 1953 is also a wonderful read.

Budget cuts were a big deal in 1953, and the military’s refusal to specify firm requirements on aircraft carrier nuclear propulsion led to the suggestion to shift the prototype project to a commercial demonstration. By removing the naval requirements, $60 million could be saved. Thus, the Shippingport reactor became the first commercial-scale demo of a nuclear power plant.

The Shippingport project was done largely in the open, and thousands of design and testing documents were released to the public. For example, here is a 600-page summary of the Shippingport reactor.

The President and the Bomb

After the Soviet Union tested nuclear weapons in 1949, Edward Teller led the effort to accelerate the development of thermonuclear/hydrogen bombs. The life-and-death issues surrounding nuclear weaponry aroused passions and emotions among the few who were aware of the situation at the time, and deep divisions in the scientific community eventually spilled over into politics. Driven by daily fear of the Soviet Union, Teller was not convinced that the Los Alamos weapons lab under Oppenheimer was serious enough about thermonuclear weapons and advocated in 1952 for the creation of a new weapons lab for thermonuclear research. This eventually came to pass as the Lawrence Livermore National Lab.

Page 37 describes The Wheeler Incident where a detailed summary of the design and operation of thermonuclear weapons mysteriously disappeared on a train.

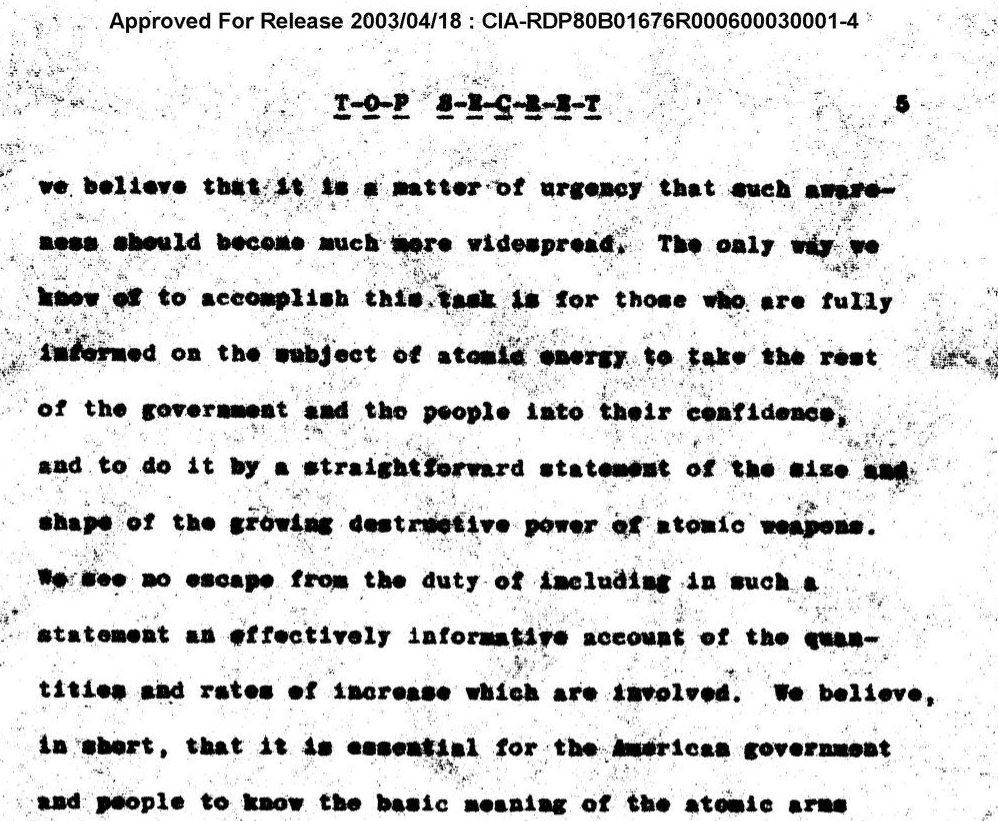

43: A Disarmament Panel led by Oppenheimer knew that the stockpiles of nuclear weapons and the destructive power of each weapon was growing at disastrous rates in the US and Soviet Union. The policy of massive retaliation only lead to a destruction of civilization. The people at large were not aware of these implications in 1953, and the panel recommended “a policy of candor toward the American people” describing how terrifying nuclear war and the arms race were.

Eisenhower was taken by the suggestion to be more candid with Americans and the world about the dangers of nuclear war. This concept drew Oppenheimer’s old rivals back together, thinking it was essential to continue to build more and larger bombs to beat the Soviets.

Around this time, Lewis Strauss became Eisenhower’s special assistant on atomic energy. Strauss was solidly in the camp against Oppenheimer and disarmament. Increasingly powerful Oppenheimer opponents were alarmed by derogatory information in Oppenheimer’s security file, where close family members were revealed to be communists. Eventually, an inaccurate and oversimplified hit piece against Oppenheimer was published in Fortune. The Borden Letter came after, which directly accused Oppenheimer of being an agent of the Soviet Union.

The resulting hearing for revoking Oppenheimer’s security clearance produced thousands of pages of information revealing lots of personal things about scientists from the Manhattan project days. Nineteen full volumes of testimony are now available for all to peruse. This testimony includes thing like first-hand accounts of the meetings where Teller first discussed his thermonuclear design ideas with the top weapons scientists.

The book goes into elaborate detail about personal interactions along these lines for at least a hundred pages…Notably, Teller’s testimony gave him a bad reputation in the scientific community.

A conflict in the administration grew. Eisenhower was very serious about Operation Candor, and Strauss wouldn’t attack it directly, though he disagreed with it.

Skipping forward, we reach the point where I started taking better notes!

The Political Arena

124 As policy questions regarding reactor development and weapons testing grew, the nature of the AEC inevitably shifted from a clear and focused military mission of producing weapons material and weapons questions of a political nature. The AEC engaged in international affairs and domestic economic matters.

135 The term special nuclear materials replaced fissionable materials in a bill in order to cover things like tritium or deuterium.

Nuclear Weapons: A New Reality

154-155 In some of the high-yield weapons tests in Nevada during Upshot-Knothole, dose rates from fallout reached 0.46 roentgens/hour and Graves ordered road-blocks to be set up and washed some contaminated cars at government expense. The Harry shot cause the most serious fallout. Local schools kept children indoors and the community at St. George came to a standstill for several hours. The community was tense.

157 After the Simon shot was unexpectedly 43 kilotons of yield, sheepmen reported heavy losses west of Cedar City, UT. Thousands of sheep died. Worried that the concern would prevent most continental testing, the AEC perpetrated a fraud upon the court by suppressing opinions of some scientists. The court found in favor of the government in 1955 based on expert testimony. In 1982 the same judge vacated the decisions as the fraud became clear.

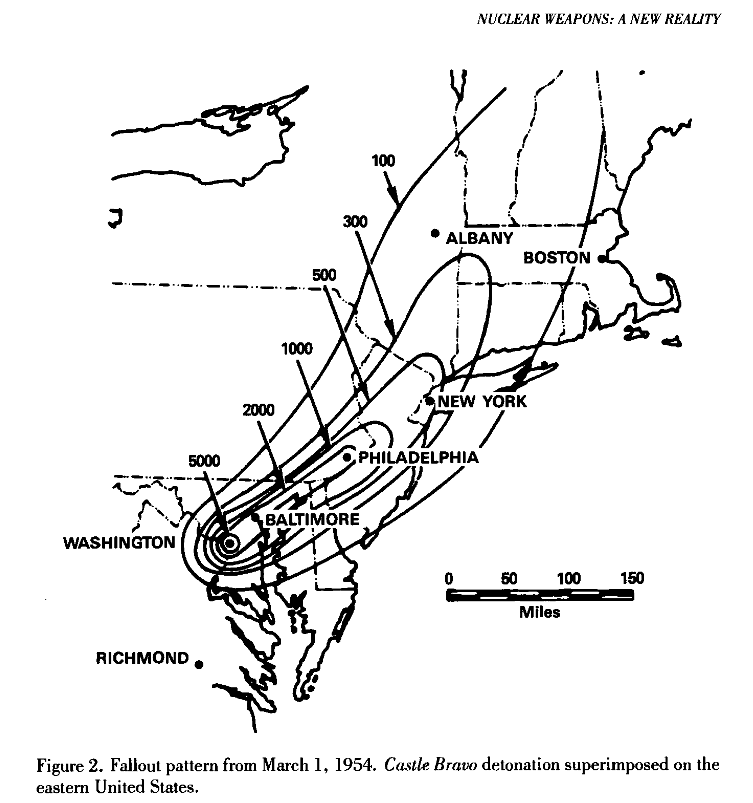

172 On March 1, 1954, the first test of of a dry thermonuclear weapon occurred. Unlike the Mike shot, this Castle Bravo test used Lithium-Deuteride fuel, which had significantly reduced tritium requirements, and did not require the vast cryogenic equipment that Mike required. The yield was 15 megatons, nearly 1000 times larger than the atomic bombs from World War II. The fallout was immense, heavily contaminating parts of the nearby atolls and the Japanese fishing ship, Lucky Dragon. Castle Bravo remains to this day the most powerful weapon ever detonated by the USA.

179 The success of the dry device allowed the weapons production complex to reduce capacity for tritium production at Savannah River and shift it to plutonium production.

181 Beyond the joy of a successful test program, the test brought a new terror to life, as the menace of city-destroying weapons was now coupled to radioactive fallout clouds thousands of miles long.

But Castle, like Upshot-Knothole, did taint the sweet taste of success with a sickening reality: man-kind had succeeded in producing a weapon that could destroy large areas and threaten life over thousands of square miles.

182 On March 31, 1954, Strauss told the world that the bomb could take out any city, even New York. This made headlines. General Fields described the fallout danger lucidly:

If Bravo had been detonated in Washington, D.C., instead of Bikini, Fields illustrated with a diagram, that lifetime dose in the Washington-Baltimore area would have been 5,000 roentgens; in Philadelphia, more than 1,000 roentgens; in New York City, more than 500, or enough to result in death for half the population if fully exposed to all the radiation delivered. This diagram was classified secret and received very little distribution beyond the Commissioners.

Nuclear power for the marketplace

185 Further consideration of “dual-purpose” weapons-producing commercial reactors was rejected by Hafstad in 1953: “the blunt fact seems to be that we are now too late for the ‘dual purpose’ approach and too early for the ‘power only’ approach.

194 Commissioner Murray concluded:

“For years, the splitting atom, packaged in weapons has been our main shield against the Barbarians — now, in addition, it is to become a God-given instrument to do the constructive work of mankind.”

195-196 In 1953, the AEC was thinking of commercializing the fast breeder, the boiling-water experiments from Argonne, and the fluid-fuel homogeneous reactor experiments from Oak Ridge. A sodium-graphite reactor was pursued by a private company, and the pressurized-water reactor effort was government-sponsored with some private industry participation. They expected the PWR to be closest to short-term success, but it produced poor long-term prospects for producing economic nuclear power. The BWR was expected to be more promising from an economical point of view. The Sodium Graphite reactor would be built on private land in Santa Susana, A. Argonne planned a second experimental breeder in Idaho. ORNL planned a modest second homogeneous reactor experiment. These last two were expected to become the most economical systems in the future.

The report explaining these prospects is 130 pages long, but I cannot find it.

201 Nichols sent the Commission a paper in 1954 suggesting a Power Demonstration Reactor program where private companies could design, build, and operate their own NPPs with limited assistance and funding from the AEC. The AEC would provide the fuel for 7 years and take the used fuel back, but would charge for any fissile material consumed in reactor. This was quickly approved and had far-reaching implications in the development of the nuclear industry.

… but more likely it resulted from the general manager’s cool and competent presentation. Nichols reduced the decision to the practical perspective of the engineer-administrator. The plan seemed a sensible first step toward a distant goal, a step that the Bureau of the Budget and the Congress could understand and appreciate.

204 People were really excited about developing nuclear power to help the world. Voorhis said:

In part the resolution of the present crisis in the world, depends on the relative success of the free world, as contrasted with the totalitarian world, in building a quality of life that is good for all its people and I believe atomic energy can play a major role in this great enterprise.

Pastore said:

Are we not trying to win the hearts and minds of people in other parts of the world? That is the great inspiration that was given to the world in the speech made by the President. Are we winning that race?

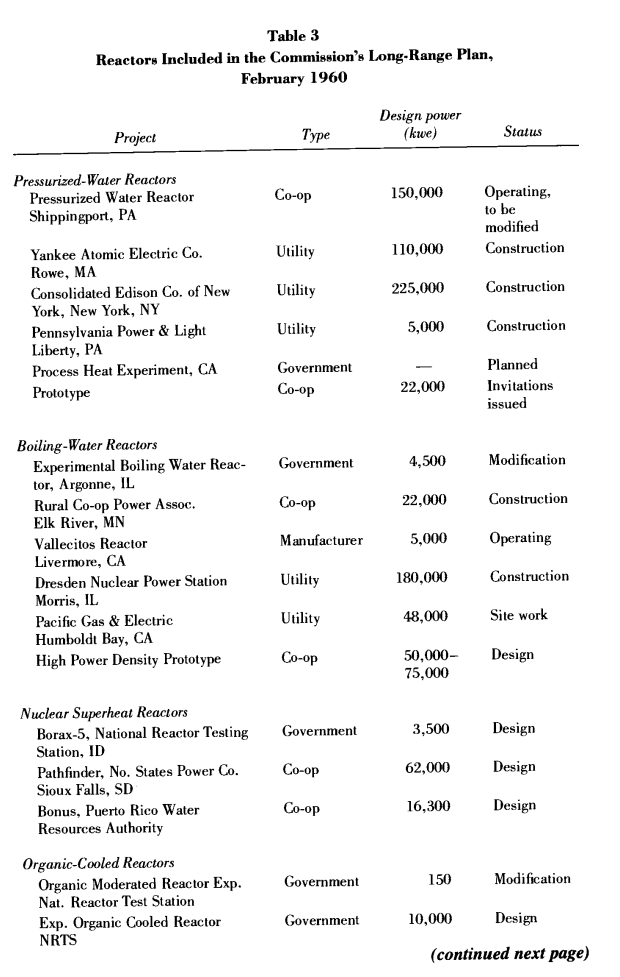

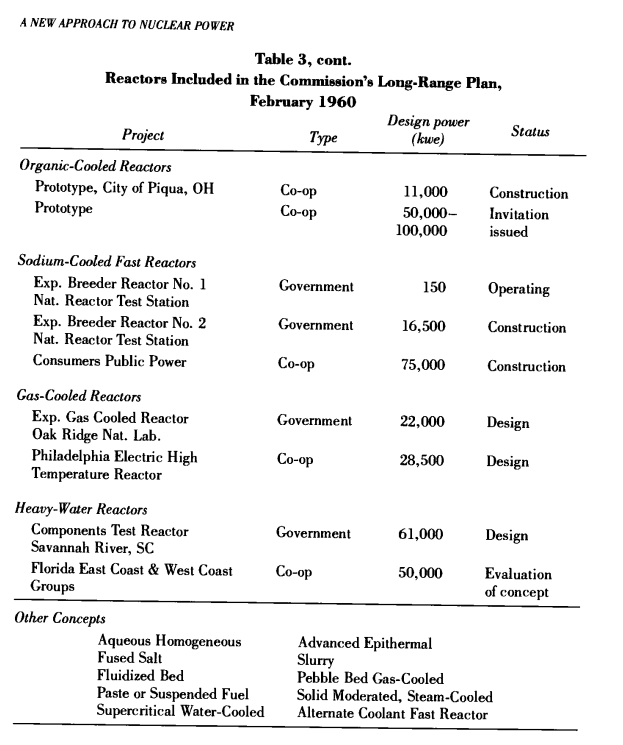

205 In Sprint 1955, 4 proposals for industry were received for the Power Demonstration Reactor Program:

- NPG with a 180 MW BWR in Chicago

- Detroit Edison with a 100 MW fast breeder in Detroit

- Yankee Atomic Electric Co with a 100 MW PWR in Massachusetts

- Consumer Public Power of Nebraska with a 75 MW sodium-graphite reactor

Strauss expected a fifth proposal for a fluid-fuel rector but it never arrived.

Atoms for Peace

211 This chapter covers the beginnings of the IAEA and lots of political maneuvering with the Soviet Union related to fissionable material, commercial nuclear, research reactors, and weapons testing. Within the administration, there was some foot dragging:

Strauss said he did not oppose the President’s proposal; he merely wished to warn that Atoms for Peace would not soon take precedence over Atoms for War.

221 The Russians criticized the Atoms for Peace proposals, calling, suggesting that the peaceful atom was an illusion and that growing electrical generation with nuclear reactors would increase the amount of nuclear materials available for weapons. The Americans assured the world that safeguards could be developed to prevent the spread of weapons from peaceful operations.

Pursuit of the Peaceful Atom

244 Eisenhower got really excited about a nuclear-powered merchant ship in 1955. Rickover basically killed it at the time by saying it would delay the naval needs.

245 Nelson Rockefeller was infatuated with small power reactors as the basis of an Atomic Marshall Plan for the world. He pushed to build more research reactors around the world and declassify reactor information. He wanted the US to help India, Japan, Brazil, and Italy with power reactors immediately. The AEC and State Dept were not excited about it. They dragged their feet and effectively killed the enthusiasm.

252 First Commercial nuclear regulations were drafted in 1956, attempting but uncertain if they struck the right balance between protecting the public and giving companies the freedom needed to commercialize the technology.

253 The Brookhaven lab was the closest to reaching the original ideal of regional academic center with partnerships with nearby universities.

257 The technology of strong focusing enabled much higher-power particle accelerators.

258 Discussion of what I assume led to Fermilab. Apparently Walter Zinn at Argonne got really dramatic and resigned because the plan didn’t include the Argonne lab enough in high-energy physics.

261 Discussion of fusion power

263 The AEC spent lots of money on cancer treatment research and biological work. Tracer studies with radioisotopes furthered understandings of biological systems and effectiveness of drugs extremely well.

Along the way, studies on the biological effects of radiation were broadened. The AEC focused some studies on fallout, including when radioisotopes are uptaken into organ systems.

265 Project Gabriel studied short and long term effects of fallout to understand the implications of a nuclear attack.

266-268 The Muller Fiasco is described. Hermann Muller had won a Nobel Prize in 1946 for his work on the effects of radiation on genetics. He was scheduled to present a paper at the Peaceful Uses conference in Geneva, 1955 on the topic. He had give a lecture at the National Academy of Sciences called “The Genetic Damage Produced by Radiation”, and gave a copy to the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. The paper was moderate and judicious. He criticised both those who discount any genetic damage from blast victims of Japan, and also those who loudly claimed that weapons tests are undermining the genetic basis for all mankind. He urged efforts to minimize fallout, but unequivocally supported testing them for national security reasons. The paper was submitted for Geneva, promptly accepted by the American scientists, and scheduled. But then Muller’s invitation was revoked ostensibly because he had been an active socialist during his youth in the Great Depression in NYC. This caused an outcry of protests from the American scientists. The AEC’s credibility was damaged yet again, as it appeared to be suppressing discussion of genetic effects of weapons testing.

269 The Dixon-Yates issue is mentioned for the umpteenth time. This is likely one of the main issues that politicized nuclear power across party lines in the USA. It’s basically about government-funded vs privately-funded power plants

The Seeds of Anxiety

277 Churchill, after learning about how bad nuclear weapons had gotten, abandoned expensive air raid shelter work since they would not help in thermonuclear war.

280 Foster thought that thermonuclear realities would eventually require a radical change in the way we design cities. We’d have to eliminate densely populated metropolitan areas altogether.

286 Eisenhower wanted to enlist the best advertising man in the country to find out how to best discuss the issues of fallout with the country. The CEO of Coca Cola was consulted, but upon hearing about it, recommended not talking to Americans about it at all! Hilarious.

287 AEC report on fallout was painted by Lapp as a hesitant response to his crusade for more info from the Bulletin. Lapp characterised radiation as a mystical invisible killer.

288 Congress and Lapp didn’t know that the State and Defense Depts had been holding up the AEC’s fallout report for so long. This just continued to erode public trust.

290 The public blamed unseasonable snow on the Operation Teapot tests, and the fallout was detected all around the country

291 The Soviet Union participated heavily in spreading fear of fallout and radiation in general in order to slow down US progress in weapons design. They were behind and needed the US to delay so they could catch up.

293 Apparently antibiotics can cause genetic mutations too.

296 These authors are great:

But as in tempering steel, the more the commission threw cold water on the linkage the harder it became.

304 Pope Pius called for an end of nuclear testing, embarrassing the AEC because they couldn’t claim he was politically or ideologically motivated.

307 A moral imperative to find redeeming value in the engineering successes of nuclear weapons drove Eisenhower to obsess over progress in Atoms for Peace.

312 It was thought that proper safeguards and inspections in a reprocessed system with fluids might be actually impossible.

316 A task force conceded that any large dedicated country could make a nuclear arsenal if they wanted to. Russians continued to say Atoms for Peace could spread nuclear weapons skills to underdeveloped small countries as well.

332 Dulles feared that the nuclear paradigm would decrease the value of being an American ally.

341 Linear No Threshold dose response model agreed upon by most geneticists in 1956.

343 As much as Democrats like public power, the drive of Al Gore Sr. was to make power reactors to compete with the Soviets.

344 Debate on the Gore-Holifield bill sounds interesting. The AEC and Administration and private industry fought the Democrats desire to have the AEC build power reactors on AEC sites to power the AEC sites. The bill was defeated in the House and killed the chances for a nuclear power bill in the 84th Congress. Democrats had dreamed of a national energy policy but now the dream was in shambles. Anderson became even more suspicious of Strauss’ motives, and began suspecting that he was opposed to nuclear power because it would threaten the economic interests of his friends in the fossil industry, the Rockefellers.

345 More understanding of fallout to the public after the Redwing test series where we tested our first airdrops of multimegaton thermonuclear bombs. The Army chief of R&D confirmed that a recent Fortune article was correct in that a large attack would kill 7 million Americans and render hundreds of square miles uninhabitable for perhaps a generation (largely from Sr-90). Worse:

Gavin predicted that American retaliation against Russia would spread death from radiation across Asia to Japan and the Philippines. Or if the winds blew the other way, an attack on eastern Russia could eventually kill hundreds or millions of Europeans including, some commentators added, possibly half the population of the British Isles.

This classified testimony was released on June 28, 1956, further informing the startled public of the implications of nuclear warfare. The President’s advisers and the AEC started promoting the development and testing of “clean” nuclear bombs, which could be designed to have much less fallout.

347 Strauss’ talk of clean nuclear weapons exposed the AEC to scathing criticism from the press.

Ralph Lapp wrote a devastating critique in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, when he observed that Strauss single-handedly had invented “humanitarian H-bombs.” … “War is a dirty business,” Lapp observed. “Part of the madness of our time is that adult men can use a word like humanitarian to describe an H-bomb.”

Nuclear Issues: The Presidential Campaign of 1956

351 The 1956 election campaign vs. Stevenson was the first election where nuclear issues were prominently featured. Eisenhower easily won, but the AEC, its leadership, and its programs payed a political price and lost more public confidence.

353 The EBR-1 core meltdown raise safety concerns regarding the Fermi 1 fast reactor project near Detroit. The ACRS warned the general manager that more study of the Idaho accident was needed before Fermi 1 should proceed. The AEC worried that delay in Fermi would undercut progress in power demonstration. Political fights between the AEC and the Joint Committee lead Anderson to tell the governor of Michigan of the situation, but the AEC still didn’t want to release the report. Anderson was so angry that he suggested that the new Congress should consider legislation that would separate the AEC’s licensing and regulatory functions from its research and production responsibilities. This foreshadows the eventual split of the AEC into the NRC and the DOE.

359 The Piqua organic-cooled reactor in Ohio and the Consumers Hallam sodium-graphite project in Nebraska were approved, partially to blunt the charge by the rural cooperatives that the AEC was favoring big private utilities.

The AEC at this time was worried that once the government funded some nuclear development costs, private industry would expect it to fund all future development costs too.

Strauss immediately voiced his concern that, once the Commission opened the door, there would be no way to close it.

The AEC agreed that winning the international race in reactor development was more important that keeping the government out of nuclear power.

Looking back, there’s some truth to this; private industry for a long time expected the government to pay the big bucks for nuclear developments. Private startups today almost ubiquitously depend on large government development programs.

365 In the campaign, Eisenhower said he would not endorse any “theatrical national gesture” to end weapons testing without reliable inspection, and said this great line:

We cannot salute the future with bold words while we surrender it with feeble deeds.

366 In response to Eisenhower trying to be final, Stevenson said that there can be no last word in the hydrogen bomb until mankind had been freed from the menace of nuclear incineration.

367 Stevenson had a way of describing the power of nuclear bombs.

He noted the power of a 20 MT bomb — as “if every man, woman, and child on earth were each carrying a 16 pound bundle of dynamite — enough to blow him to smithereens, and then some.”

He also described strontium-90 as the most dreadful poison in the world. He wanted to stop the tests before a maniac like Hitler or other irresponsible regimes fouled the atmosphere with tests of their own.

369 The AEC wanted to help disabuse the public of Stevenson’s inaccurate campaign statements about the biological effects of radiation. They agreed to use their speaking engagements to present correct technical information.

In Search of a Nuclear Test Ban

373 Soviet Premier Bulganin wrote a political letter to Eisenhower to interfere with the American election. Some things never change.

379 Senator Neuberger proposed an independent institute responsible for studying nuclear health. The AEC opposed this, suggesting it would duplicate facilities. Clearly, military atmospheric testing was damaging world opinion.

390 Albert Schweitzer, a famous doctor/musician/philosopher came over Radio Norway to advocate the banning of nuclear weapons tests. Professors joined in. Linus Pauling said so during an address to Washington University. Lots of Nobel Laureates. They said we shouldn’t devastate the beautiful world in which we live.

395 Stassen, trying to negotiate with the USSR all the time, was a total cowboy and did stuff against the administration’s will. He probably had political motivations.

397 It was feared that as bombs became smaller and cheaper, places like France would see less value in NATO and the American Atomic Shield.

399 The weaponeers, Teller and Lawrence, had moral justifications for additional atmospheric testing. They said we knew how to make dirty bombs of unlimited size, and if war came, we’d have to use them (God forbid). But if we keep testing (at minimal risk), we can make better bombs that can be limited to military targets without destroying the planet. Clean bombs offer big military and psychological advantages.

At this point, plutonium was considered far superior to highly-enriched uranium for weapons.

400 Teller warned senators of ways to muffle subterranean megaton blasts and upper atmosphere testing during a test ban. If the Russians developed clean bombs first, he said, we’d be in real dire straits.

Lilienthal was disgusted at the mega-bomb proponents marching to D.C. saying what Oppenheimer had said before: we need small tactical bombs.

Politics of the Peaceful Atom

404 The Suez Crisis in Fall 1956 and the Hungarian revolution got the EURATOM negotiations back into high gear, emphasizing the need to develop nuclear energy as rapidly as an alternative to Middle Eastern oil. A committee of three was appointed to formulate a politically and technically feasible nuclear power program to meet this need. The Three Wise Men were Louis Armand of France, Franz Etzel of Germany, and Francesco Giodani of Italy. At this time, Europeans agreed that the French could develop nuclear weapons if they’d share access to weapon research and development and the weapon stockpile.

406 Europe was facing the import of 100 million tons of coal annually, increasing to 300 million by 1975. They would be able to pay 9-12 mills/kWh, which was higher than the Americans. The AEC thought American reactors might find a market in Europe for this reason.

American efforts in the power demonstration program had proven that the private industry in the USA could not finance the development of commercial nuclear power.

… industry had badly underestimated the difficulties involved in designing and building nuclear power plants.

Inflation and rising cost estimates were dampening industry interest in nuclear power. The Shippingport unit under construction had escalated to be 5-10x the costs for fossil-fueled plants. Meanwhile the UK’s gas reactor program was focused.

Shippingport was hardly an attractive selling point for American technology.

410 Still angry about the defeat of Gore-Holifield, democratic senator Anderson held up the insurance indemnity bill, which nuclear manufacturers demanded, until the AEC became more cooperative. Through political maneuvering, the first, second, and a new third round of the Power Demonstration Reactor Program was approved, a Plutonium recycling experimental reactor at Hanford, and studies of a natural-uranium, graphite-moderated, gas-cooled power reactor were authorized.

The Price-Anderson Act was then introduced and quickly passed. It requires operators of large power reactors to carry the maximum amount of insurance available from private companies and indemnifies them for $500M over the private coverage. At the same time, the ACRS was transformed into a statutory body and its reports were made public.

Morale was low for the nuclear industry in 1957. The Five-Year Plan reactor had twelve government projects now, but of the 5 reactors that operated, 2 had serious design flaws, 2 were just starting up, and the fifth was a test device. None had suggested a promising new approach to nuclear power. The Power Demonstration Reactor Program wasn’t doing much better. Several private companies were operating privately funded reactors at this time as well.

413 Walter Zinn told Strauss that he was convinced that the US’s concentration on water-cooled reactors with enriched fuel was a mistake. He favored natural-uranium reactors using a liquid coolant like sodium. He was frustrated that the AEC waited for industry to decide on reactor designs rather than guiding the direction.

The Elk River estimates soon exceeded the allowed ceiling. Foster Wheeler Corp backed out of the Wolverine fluid fuel project. Confusion broke out in the industry. The AEC convened a reactor advisory group in October ‘57 to discuss the economic potential of nuclear reactors.

414 The advisory committee said that capital costs in water-cooled plants can only be reduced by increasing the power. They determined that a long campaign of patient and painstaking development was the likely pathway to nuclear power, not dramatic technical breakthroughs. Even then, capturing economies of scale was likely the only credible path forward. There was too much breadth and not enough depth in the current reactor programs.

Davis presented these findings at the Atomic Industrial Forum in NYC, saying new reactors would be the most economical in the long run, but that early economics would be found in very large installations of water-cooled reactors.

418 By December 1957, a series of industry conferences said otherwise. Utility executives did not et know enough about the various types of reactors to commit themselves to one concept. They wanted orderly R&D into alternatives to water reactors rather than rushing into investments in large reactors that would produce very expensive power. This disagreement caused some fracture in the industry as a whole.

421 Rickover ended up getting Shippingport up and running on December 2 1957 (15 years to the day after the first chain reaction at CP-1). The utilities hated him. He was egotistical and demanded grueling shift work. But he got stuff done. In the end, it cost 64 mills/kW, compared to 6 mills/kW for a comparable fossil plant.

422 Thousands of engineering documents from Shippingport are publicly available.

423 The Navy went all in on nuclear submarines, and Rickover set out to deliver. He trained the suppliers to accept the rigid requirements as both attainable and necessary. He put in place quality assurance programs at suppliers. He realized economies of mass production. While the commissioners debated policy, Rickover built a network of companies upon which the nuclear industry would depend.

424 More discussion of dual-purpose reactors?!

429 Strauss’ principles of keeping government out prevented the AEC from putting together a comprehensive strategy and left the AEC weak.

Euratom and the International Agency, 1957-1958

433 Conservative David Teeple led drive against the IAEA, calling it the “President’s fantastic Atomic Energy giveaway plan”

440 With Sputnik launching in 1957, some wanted to use atomic energy as an international bellwether of american scientific preeminence.

Toward a Nuclear Test Moratorium

451 More talk of Russians spreading fear of radiation to help them catch up in nuclear weaponry.

452 In 1957, Shute published On the Beach, an apocalyptic novel about the world laid to waste by radioactive fallout. This was turned into a few movies. A nuclear submarine captain and crew survived and are in Australia. Everyone knows they have only a few months to live before the radiation comes down to them. They go to Seattle but it’s a barren wasteland. Everyone commits suicide in the end. I need to watch/read this.

483 A Quaker group set up camp near Nevada Test Site to protest. They got arrested. Pacifists organized into SANE, and lobbied for a test ban. They planned to sail the Golden Rule to the Pacific Proving Grounds to stop the Hardtack test series. They got about a mile from Honolulu before getting detained by the Coast Guard. It captured public and press attention.

484-485 A group came to the lobby of the AEC headquarters and said they would fast there until they could speak with the Commissioners. The AEC said they could stay there indefinitely and provided cots, blankets, a telephone, and a washroom. Sandwiches, coffees, soda were offered, and everyone was friendly. They waited a week. One commissioner volunteered to talk to them, but this wasn’t good enough for the protestors. They wanted to see Strauss. Strauss agreed, and the unusual meeting occurred. The protestors appealed to Christian-Judaic tradition and to Ghandi. It was on high moral ground. Strauss was moved, and remarked how in WWII he refused on moral grounds to invest in munitions or distilleries. But the holocaust convinced him that only America’s great nuclear deterrent had saved the world from communist domination. The group disagreed and said the US should not have fought the Nazis. Strauss (a Jew) asked if the Civil War was justified. The pacifists said “No. The body is nothing. Only the freedom of the spirit mattered”. The dialog ended here. The demonstrators ended up in front of the White House.

Strauss had already resigned at this point, and McCone took over.

488 Edward Teller explained that underground testing would not hamper the weapons program at all. This may allow the US to unilaterally ban atmospheric testing.

A New Approach to Nuclear Power

492 McCone said dual-purpose (commercial + weapons) reactors were unacceptable.

494 McCone worried that GE and Westinghouse were not as rigorous on their commercial projects as they were in the naval projects.

495 Zinn and Smyth published a national nuclear power policy in August 1958

Panel wanted commission to take on positive direction and stop asking private industry to say which types of reactors they liked best.

497 Rickover thought the quest for economic central station power would threaten public safety.

504 McCone wanted the kind of solid data that engineers and businessmen needed to make sound decisions about nuclear power. He canceled the Alaska SFR at Churgach but continued the Hallam Nebraska one even though it wouldn’t produce good engineering data.

505 McCone was not excited about the Joint Committee’s request for gas-cooled reactors because they were too different from what we new. He was also not excited about fluid fuel reactors for similar reasons.

506 The Merchant Nuclear ship NS Savannah originally was supposed to have a clone of the Nautilus core but Rickover said this was not appropriate. B&W did a new design. They didn’t ask the Navy for any experience info. McCone asked the Navy to review the design. Press thought Rickover was trying to take over, but he wasn’t. Rickover listed the ways it was different from a Naval system but didn’t find any major design flaws.

508 More talk and references about evaluating the promise and future of nuclear reactors.

509 Coal prices fell in Europe, tempering the earlier demand for nuclear.

Breeder reactors were expected to be needed in 50 years. Therefore, they were not a high priority.

511 An industrial process heat experiment with a PWR in California was planned. I wonder what happened with that.

Science for War and Peace

516 Sputnik got science advisors on the highest government positions they’ve ever had before or since.

517 Aircraft reactor interest revived after sputnik but wasn’t looking promising. Many recommended cutting the budget.

518 Mention of Kennedy killing the Nuclear Aircraft. This is what Weinberg said as well.

519 Science advisors didn’t like the lab’s projects Pluto and Rover for nuclear rockets and missiles and ramjets, especially considering the progress in conventional jets.

SNAP series RTGs and small reactors were very cheap and very successful. Helped by Sputnik as well, of course.

520 Brief mention of the Army Nuclear Power Program. Small and cheap. They didn’t command the attention of McCone, York, Kistiakowsky, or the president. ML-1 barely mentioned, Plus a small BWR? What’s that?

521 Nuclear navy went on crazy adventures to the north pole and whatnot, like Jules Verne-level adventures. The Triton circumnavigated the earth without surfacing (Operation Sandblast).

526 Politics and money cannot always drive technology (regarding fusion power)

529 Some talk of Project Plowshare and peaceful nuclear explosions

532 Rickover went to Russia to ride on the Lenin icebreaker with VP Nixon. He lost his security detail and talked to people at will. What a character.

536 Stuff about Russia cooperation. We agreed to study nuclear waste disposal with them.