What is a Microreactor?

By Dr. Nick Touran, Ph.D., P.E., 2026-01-24, Reading time: 13 minutes

Microreactors are small, low-power nuclear fission reactors that make less than 10 megawatts (MW) of electricity (or ~30 MW of heat). Numerous efforts to develop and deploy microreactors are ongoing with hopes to achieve breakthroughs in how nuclear power is utilized by humanity. They are characterized only by power level, and may use any coolant or moderator combination.

Why microreactors?

Excitement about microreactors is prevalent in the private sector (numerous startups), the civilian government (the US Dept of State Project Phoenix and Dept of Energy pilot program), and the military (Pele and Janus). What makes people think micros are a good idea?

1. Microreactors can be applied to novel power markets

Nuclear’s unique energy density enables microreactors to deliver relatively huge amounts of power in applications where it is otherwise unavailable, such as in remote locations, underwater, far out at sea, in orbit, and on extraterrestrial bodies like Mars, the moon, and beyond.

Historical microreactor development has focused on remote and military applications. In the 1960s, the Army Nuclear Power Program deployed microreactors to remote bases and radar stations in Alaska, Wyoming, Antarctica, and in an ice base in Greenland. The Soviets put a few dozen nuclear reactors in orbit to hunt for American submarines with high-power instruments, while the US only put one reactor in orbit (SNAP-10A). Reactors like TOPAZ-II were developed and tested for orbital or extraterrestrial use through the 1990s.

The smaller size and weights of microreactors make them ideally suited for transportation to remote areas. The truck-mounted ML-1 military microreactor was designed for forward operating military use in the 1960s, but was too unreliable and uneconomical (10x more expensive than oil) to survive back then. Today, something like 50% of military losses are related to vulnerabilities of oil logistics. Nuclear-powered liquid fuel synthesis energy depots for military convoys were developed in the 60s but also abandoned. Higher power military equipment (lasers, drones, communications) are adding more demand for military power than ever. The cost premium that the military is willing to pay for compact, high-density nuclear power is ripe for another round of consideration.

2. Manufactured products, not construction projects

Nuclear power today is widely recognized as safe, reliable, clean, and long-term sustainable. Its one remaining challenge is cost. The physically small nature of microreactors allows them to leverage economies of mass production: using assembly lines rather than bespoke construction megaprojects. Similar factories have demonstrably enabled efficient production of aircraft, motor vehicles, solar panels, wind turbines, computer chips, and thousands of consumer goods. Most excitement about microreactors today orbits around the dream of productizing nuclear reactors.

Product manufacturing can be controlled by one entity. Even without vertically integrating the entire supply chain, having your own assembly line that you run as a single company can have huge advantages over complex multi-party megaproject management, where the owner/operator, reactor vendor, constructor/EPC, and hundreds of other construction contractors are working with divergent motives. The hope here is that such an arrangement can reduce administrative burden and overhead enough to overcome the diseconomies of scale.

3. Microreactors are within reach of private capital

A big 2000 MWe nuclear project can cost well upwards of $30 billion. While it will reliably provide power to 2 million people for 80 years on a tiny footprint, it’s hard to imagine venture capitalists getting involved in such a thing. These projects are typically financed by massive consortiums of utilities, with federal loan guarantees and other backstops.

But if you’re developing a little 1 MWe plant, maybe designing, qualifying, licensing, and building the first one will only cost a few hundred million. This is within reach to the VC community, and if you can get them to imagine a world where the first one runs well and leads to factory production of thousands, the upside is clearly intriguing. In any industry, serious VC interest brings flair, hype, excitement, and a whole lot of FOMO. The CEOs of the microreactor companies always have the best tweets, and give the best mic-dropping speeches at conferences and on podcasts.

4. Microreactors have less radioactive stuff that could leak out

In a fission reactor, the power generated is directly correlated to the number of atoms you are splitting per second according to the formula:

\[\text{Power [watts]} = \text{Fission rate} \left[\frac{\text{fissions}}{\text{s}}\right] \times 200 \left[\frac{\text{MeV}}{\text{fission}}\right] \times 1.602 \cdot 10^{-13} \left[\frac{\text{joules}}{\text{MeV}}\right]\]Fission rate is, in turn, directly proportional to the primary safety challenge in any modern reactor: afterglow heat. So if you have lower power, you will have less decay heat to remove in accidents. If you explode or melt down anyway and release all the radioactive atoms, there will be fewer of them.

Thus, if you’re just building one small reactor, it seems reasonable that the regulatory scrutiny could be less onerous. That said, if you want to build 1000 microreactors instead of 1 big one, the aggregate radiation release rate of all 1000 together should match or be less than that of the one big one. In other words, it’d be about even if each microreactor were about 1000x safer than each big reactor.

What are the challenges?

As always, there are downsides.

Diseconomy of scale

Economies of scale are real. Consider one big 1000 MWe reactor compared to 1000 different 1 MWe microreactors. The gigareactor has one reactor vessel, one control room, one biological radiation shield, 2-4 primary coolant pumps, one set of control rod drives, etc. It can be operated by a team of like 5 people in the control room.

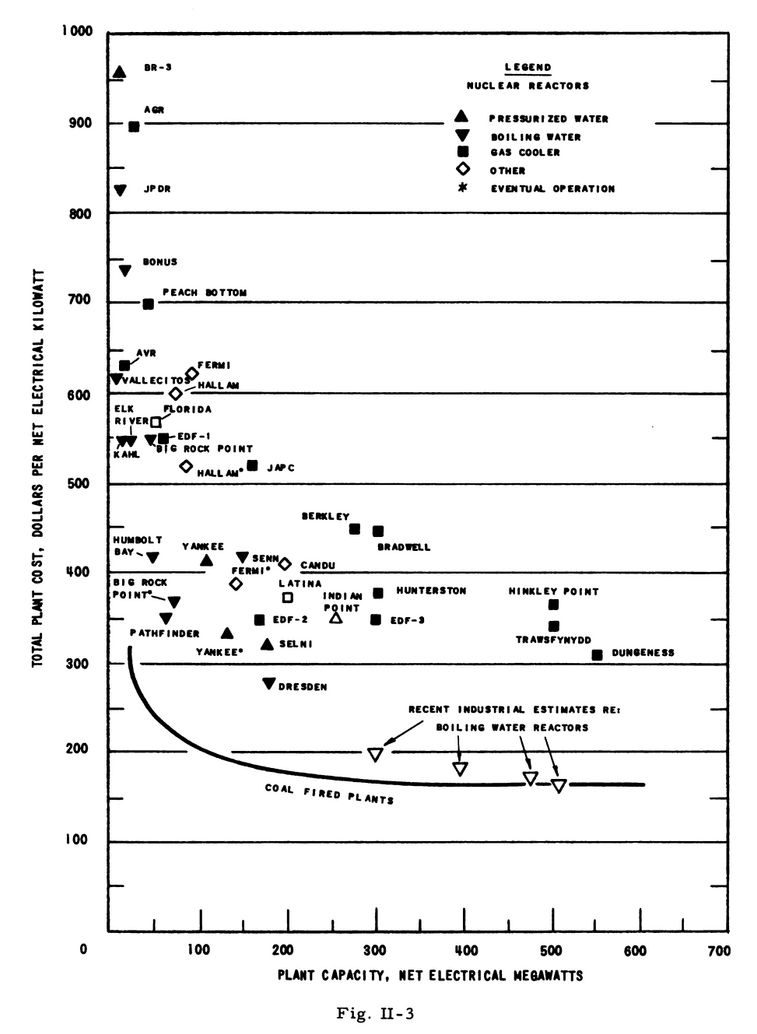

Meanwhile, the fleet of 1000 reactors will have just about 1000x more coolant pumps, sensors, control systems, control rod drives, and radiation shields. There are 1000x more components to be inspected and signed-off on, with 1000x more paperwork from those inspections, (per unit of energy generated, of course). There will be 1000x more fuel insertions and removals. Right away, you need each of these things to be about 1000x cheaper than their larger counterparts to break even. In reality, we’ve found again and again that you can fabricate a vessel that can handle 10x the power for much less than 10x the cost. This effect was real in 1961 and it’s still real today.

Historically, this has driven reactor powers up. We started out with small reactors and made them bigger to achieve better overall cost, measured in dollars per kWh generated. More recently, numerous SMR vendors, including NuScale and Oklo have uprated their designs specifically to reduce the overall cost.

Outside nuclear, we know that GM alone manufactures 200,000 MW of internal combustion engine capacity per year for vehicles using ultra-optimized assembly lines and a lean global supply chain. Yet, zero of these engines are used for electricity generation. Why? Because the big fossil-fired generators are so much more efficient, economical, and effective thanks to economies of scale.

This reality does not matter at all in novel power markets discussed above, where transportable nuclear energy density offers truly unique capabilities in remote areas. However, when talking about commodity energy markets like powering data centers or making electricity for the grid, the likelihood of microreactors competing with larger reactors or other power systems appears to be quite low.

Some of the hype out there where people claim their mass-produced microreactors will make sense in commodity markets have not convincingly argued that they really can deliver at the required price point. While some overhyping is normal, these kinds of arguments can inadvertently undercut the deployment of highly-optimized time-honed top-notch all-American workhorse reactors that are already proven and have fully licensed designs (like the AP1000 AND ABWR).

The tyranny of neutron diffusion

Neutrons in a bare cylindrical reactor take on a cosine shape axially and the shape of Bessel functions radially (like a vibrating drum). Enrichment zoning (i.e. higher enrichment on the outer edges) and neutron reflectors can flatten this natural shape to a degree, but never entirely. Neutrons travel a given distance based on the coolant and moderator choice regardless of the core dimensions (see moderation). Thus, the laws of physics demand that smaller cores leak more neutrons out than larger cores. When you’re leaking more neutrons, you need more fuel to run per power generated, and you run with a more ‘peaky’ power and burnup distribution, which means you reach your material-constrained burnup limit at the peak position while effectively wasting fuel atoms at the tips and edges. You can try to optimize fuel management, 3D shuffling, whatever to make this better, but so can larger reactors, and larger reactors will always win. So, the overall fuel cycle efficiency is worse in small reactors. This leads to higher costs and more nuclear waste, per kWh.

Furthermore, to keep size small, many reactor vendors crank up their required fissile concentrations well into the ‘HALEU’ zone (medium-enriched uranium rather than low-enriched like the big neutronically-efficient water-cooled reactors). This adds additional fuel cost premiums and brings in major new supply chain risk. At the moment, all reactor vendors who put forth designs that require HALEU are counting on the US Government to provide it. An interesting design choice, to be sure.

You can get a feel for how significant these effects are with the interactive Neutronics Scoping Tool.

The size and weight of radiation shields

Simple geometric considerations related to surface area and volume suggest that the relative amount of shielding material needed in smaller reactors is a lot higher than in larger reactors. The inherent material requirements are more demanding. The smaller you go, the worse this gets.

Shielding any kind of mobile or transportable reactor of any size is seriously challenging if you want people anywhere near it, and if you want to avoid activating the surrounding soil (which can leave contamination wherever you operate. In this article, I discussed the shielding design and performance done for the ML-1 military microreactor. Its internal shielding included 2 inches of lead, a layer of ‘shield solution’, more lead, and 2 feet of 2% borated water. Optimization suggested putting 3” of tungsten in there with the lead. With that shielding, you’d get:

- 269 mrem/hour standing 100 ft away during operation

- 69 mrem/hour standing 25 ft. away after shutdown

- 3.3 mrem/hour standing 500 ft. away from activated shield materials alone(!)

For reference, 100 mrem is the yearly NRC dose limit to the public, and natural background dose rate is about 0.035 mrem/hour. These are serious dose rates. You should always treat renderings of operating reactors with people walking around them with serious skepticism unless you see a good 8 ft. of concrete or so surrounding the core in all directions. Notably, it’s a rich tradition for even experienced reactor designers to seriously underestimate the required shielding. Countless reactors have first turned on at low power only to require sometimes years of retrofitting to put sufficient radiation shielding in.

Of course, the required amount of shielding is heavy and difficult to transport.

Conclusions

Microreactors are a fast-moving, exciting, and interesting sector in nuclear. A dozen are racing towards criticality in the DOE pilot program. With the progress we’re seeing, I have no doubt that more than a few will achieve criticality on that timeline. This will lead to more people getting more hands-on experience with new types of reactors than we’ve had in decades, which is an absolute and excellent win.

The microreactors will probably not run economically or reliablly at first, but since they are small and relatively cheap, design iterations can be executed quickly and economically. This is another major advantage of the microreactor scale: it allows for (relatively) rapid iteration and learning. Microreactors may be the best platform upon which to shake down various design solutions related to advanced reactors using less common coolants (helium, molten salt, liquid metal, organics, etc.). Their low-power nature enables iteration without undue regulatory burden.

If anyone eventually does produce reliable microreactors, their potential in novel power markets is unbounded, particularly in space. High-power space applications that we can’t even think of right now may be unlocked by such a development, though we certainly can imagine lunar and Mars power in the short term.

Their potential in commodity energy markets is much worse, for the reasons discussed above. If a reliable advanced reactor is developed in a micro-scale, then that’s the ideal place to start scaling up from to capture economies of scale and compete in the traditional commercial markets.

In summary, efforts and progress in microreactors are ongoing, may pave the way in novel markets, and may help establish new starting points for larger scale advanced reactors in commodity markets.

I wish the best to all microreactor developers!

See Also

- Microreactors, Macro Problems — A Decouple podcast where I talk about microreactors

- Shielding Microreactors may be harder than you think — article I wrote on linkedin about shielding