Nuclear reactor coolants

By Dr. Nick Touran, Ph.D., P.E., 2025-03-20, Reading time: 21 minutes

The objective of most nuclear reactors is to unleash the energy within nuclear bonds and put it to work for some practical purpose. We normally induce a nuclear fission chain reaction in a fuel material, where the recoiling nuclei of fission products deposit their vast energy locally. As the fuel heats, the laws of thermodynamics kick in to dissipate the heat to the ambient environment.

At low power levels, the natural circulation of atmospheric air can be sufficient to operate a reactor without melting fuel. Fermi’s CP-1 simply transferred its 2 watts of heat to the convecting air under the squash court.

To put a reactor to practical use, higher power is needed. Energy will dissipate naturally one way or another. If Fermi had run CP-1 at high power, the fuel would have heated up far above the melting temperature of the fuel. However, melting fuel every time you turn a reactor on is not the most practical way to put nuclear reactions to work. It’s better if you can set up a system that flows some kind of heat transfer material past the fuel so that it picks up the energy and moves it somewhere else. Such a material is called a coolant material, or just a coolant.

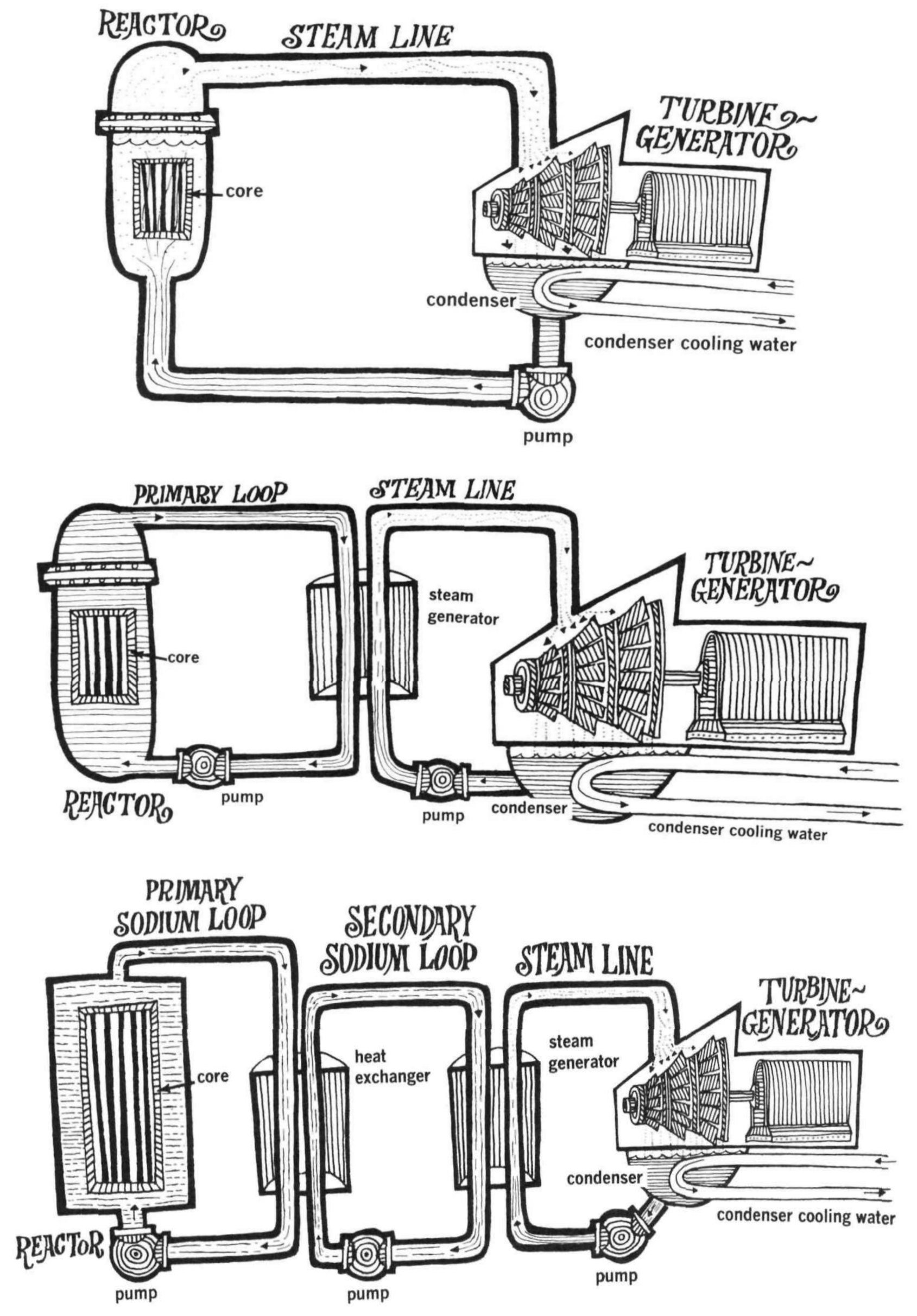

Primary vs. secondary

In many cases, the coolant that goes into the nuclear core may not be appropriate to drive the final power conversion system (i.e. the turbine). In such cases, multiple coolant materials are configured in such a way to pass the heat from one fluid to the other in heat exchangers. The coolant that picks up heat directly from nuclear fuel is called the primary coolant. The next coolant is called the secondary coolant, and so on. Some reactors only have primary coolant, such BWRs and the early Hanford plutonium-production reactors.

For example, in the close quarters of a submarine, you may want to minimize the amount of equipment that is radioactive during operation, so you might choose to keep the coolant that comes into contact with the nuclear fuel isolated in a small space and carry heat out with non-radioactive, non-activated secondary coolant. In reactors with chemically reactive coolants, three loops are common. Even more loops have been considered, e.g. four when integrating liquid metal cooled reactors with thermal energy storage systems (Fox et al., 1977).

Coolants are typically circulated in closed loops. The loops take on the same name as the coolants: the primary loop circulates the primary coolant, and so on.

WARNING To further complicate this, reactor designers often include multiple independent trains of coolant loops between the core and turbine. A “3-loop PWR” has 3 primary loops, 3 steam generators, and 3 steam lines.

Criteria for coolant selection

Parameters to look for when choosing a coolant material include generally criticality considerations as well as the following. There are exceptions based on applications, but these are desirable in general, building on (El-Wakil, 1962):

General

- Readily Available — Materials with raw inputs that are readily available rather than rare are likely to be cheaper, easier to test, easier to procure, and more sustainable.

- Low cost — All other things equal, cheaper materials (e.g. water) are preferable to expensive ones (isotopically separated liquid gold).

- Easy to fabricate/synthesize — You want the process of going from raw material inputs to reactor-ready component to be cheap and easy.

- Low toxicity — Non-toxic materials (e.g. helium, water) are easier to work with in testing, construction, operation, and decommissioning than toxic ones (e.g. molten lead, mercury, beryllium).

- Compatible with long-term waste strategy — If you plan to dispose of your materials after use in a repository, it’s best if they are chemically compatible with that repository. For example, molten salt nuclear waste may not be appropriate directly in certain deep repositories, but it may be fine to directly put it in massive salt repositories. If you plant to recycle your materials, you’ll want them to be cheaply and easily recyclable using known processes.

Thermal/chemical properties

- Good thermal stability — Materials should remain intact at high temperatures. Some candidate materials (e.g. organic coolants) can chemically decompose at high temperature.

- Low chemical reactivity — Materials should be chemically compatible with the other materials they may come into contact with during normal operation and in accident conditions.

- High heat capacity — The more energy that you can store in a core material the better. This minimizes rapid temperature changes after rapid changes in power.

- Low vapor pressure — Ideally your materials will not exert too much pressure on its container when it is brought up to useful temperatures

- Readily flows at high temperature — The coolant should be easy to move, generally preferring low viscosity fluids.

- High thermal conductivity — The easier it is to conduct heat into and then back out of a coolant, the better.

- Low melting temperature — for fluid coolants, its best if the coolant doesn’t solidify between operating modes of a reactor. For instance, many molten salts and liquid metals freeze at shutdown temperatures, which can cause flow blockages and complex stresses

- High boiling temperature — for liquid coolants, you can minimize system pressure if you can prevent your coolant from boiling.

Nuclear properties

- Low non-fission neutron absorption — The core materials should not parasitically capture too many neutrons. This implies that it have minimal impurities, to avoid atoms with large neutron appetites.

- Impact on average neutron speed — If you want a reactor with slow neutrons, you’ll benefit from materials that are good at slowing neutrons down, known as good moderators (discussed soon). If you want a reactor with fast neutrons, you’ll want to minimize materials that moderate.

- Low induced radioactivity — Neutron-induced nuclear reactions will change the core materials into radioactive isotopes. Ideally, these isotopes wouldn’t cause problematic radiation. For example, Argon in air activates to Ar-41, a beta and gamma emitter with a 110-minute half-life representing a serious inhalation hazard. In water, oxygen activates to Nitrogen-16, which, though it has a short half life, emits high energy beta and gamma rays during operation.

- High radiation stability — The core materials must not break down to rapidly under intense radiation. This is most serious for fuel materials, but structural integrity of pressure vessels, fuel cladding tubes, or other non-replaceable key components often life-limit the plant due to this.

Nature has provided us with a dizzying array of candidate coolants that all feature some complex subset of performance with respect to these criteria. Given the complex and often competing nature of the criteria, it’s unsurprising that no one coolant is optimal across the board for any given application. Thus, nuclear reactor development history has involved hundreds of ideas and thousands of experimental developments and cost/benefit analyses, and (more recently) millions of arguments in discussions online.

Water

Water is, by far, the most common nuclear reactor coolant in use today.

Pros:

- Widely available

- Cheap

- Used widely across industries

- High heat capacity, can carry lots of heat at modest flow rates

- Low viscosity, easy to pump

Cons:

- Can be corrosive if chemistry not carefully controlled

- High vapor pressure: requires thick-walled vessels and high pressures to use at high temperature

- High activation during operation

In terms of radioactive activation, water emits high radiation when the reactor is operating, but it decays away quickly after shutdown. The relevant (n,p) nuclear reaction from Oxygen-16 is:

\[\text{O}^{16} + \text{n} \rightarrow \text{N}^{16} + \text{H}^1\]\(\text{N}^{16}\) has a 7.3 second half-life and therefore emits the vast majority of its radiation within minutes after shutdown. However, it emits 10.5 MeV beta particles and up to 7.1 MeV gamma rays. Thus, any piping containing this material must be heavily shielded if equipment nearby is to be inspected or maintained during operation.

Pressurized Water

Reactors that keep water under high pressure so as to not bulk boil inside the reactor vessel is a Pressurized Water Reactor (PWR). See Reactors for more info.

Boiling Water

A light-water moderated, water-cooled reactor that lets water coolant bulk boil in the reactor itself is known as a boiling water reactor. See Reactors for more info.

Heavy Water

One out of every 3200 water molecules in nature isn’t actually regular old H₂O, but has an extra neutron attached to one of the H’s. Hydrogen with an extra neutron is called Deuterium, or D, and these molecules made of HDO are called semiheavy water (it’s water that weighs one extra neutron more). Through an industrial distilling process, we have grabbed this deuterium and reformed it into synthetic water that has two deuteriums: D₂O, which is then called heavy water. Deuterons have effectively no appetite for absorbing neutrons, and have been used in a variety of Pressurized Heavy Water Reactors (PHWR), such as the Canadian CANDUs, the CVTR in South Carolina, and numerous reactors at Savannah River.

Note that heavy water can be used boiling or pressurized as well.

Steam

Steam-cooled reactors, where the water is the gaseous phase, have been seriously considered in a form of fast-neutron reactor, though none of these have been built.

Liquid metal coolants

Liquid metal coolants, such as bismuth, mercury, and sodium, were among the first considered coolants to make commercial power back in the Manhattan Project. They offer:

- Excellent heat transfer — high heat capacity, high thermal conductivity, low viscosity allows for ready cooling of even compact high power density cores.

- Low system pressure — low vapor pressures mean you can heat the system up without it becoming overly pressurized. This reduces pumping power requirements over e.g. water (1/4). It also allows for thinner vessels, and can enable passive decay heat removal in accident conditions (i.e. active systems and backup power can be avoided)

- Relatively high temperature — allows for higher thermal efficiency

- The option of keeping neutrons moving fast — many liquid metals do not slow down neutrons. You can still slow them down with a separate moderator if you want, but you can choose not to if you want a fast reactor, e.g. to breed Plutonium.

In exchange for these tantalizing capabilities, you must be willing to sacrifice:

- High reactivity with air and water – generally requiring an extra intermediate loop before power conversion. This somewhat counteracts the cost savings of the reduced pressure as well as the higher temperature.

- Thermal shocks during transients – the thermal properties of liquid metals can impart extreme stresses on components during transients, necessitating the inclusion of thermal baffles to protect vessels, pipes, and welds.

- High induced radioactivity – requiring additional shielding in primary systems

- Not always liquid at room temperature – requiring heaters plus the associated sensors and controls along all piping systems to maintain clear flow paths throughout the system at all times, including accident scenarios.

- Opaque — liquid metals are generally opaque, causing some challenge in operations and maintenance.

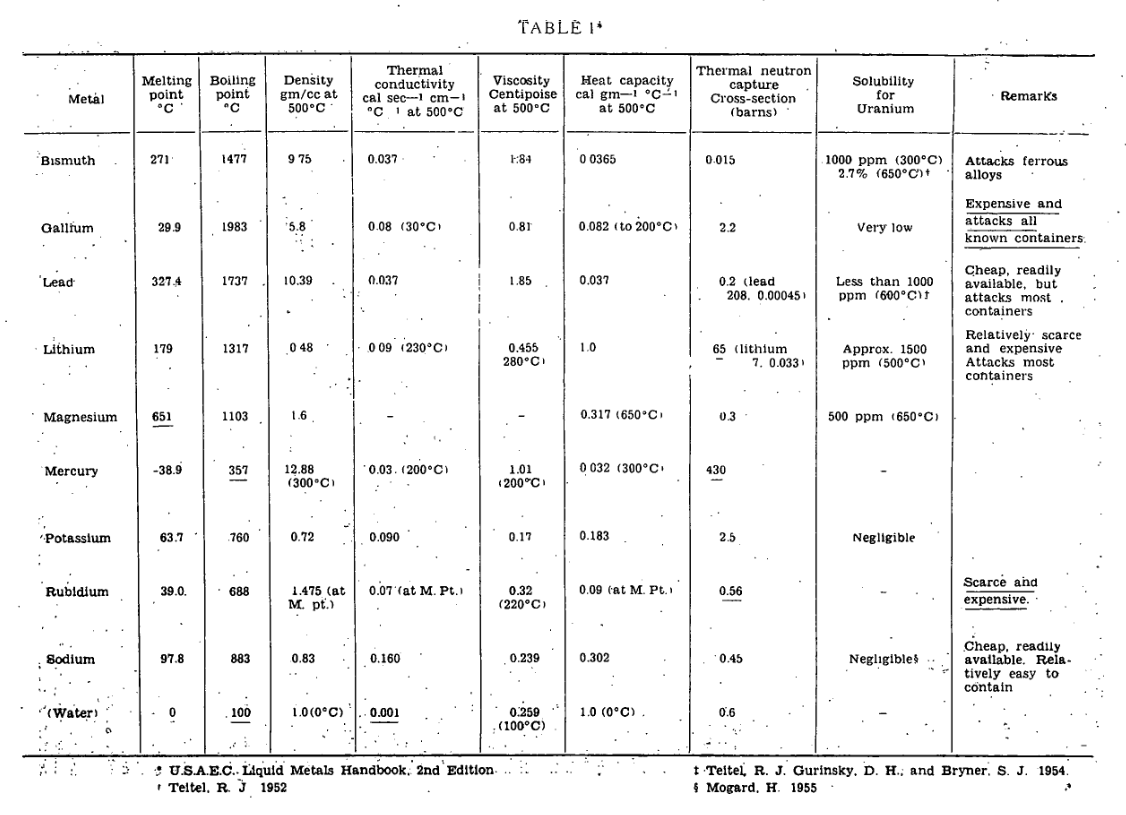

Table 1. More specific pros and cons of a handful of liquid metal coolants

| Liquid Metals | Pros | Cons | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury | Liquid at room temperature, non-reactive, common | Corrosive, toxic, poor heat transfer | Clementine |

| Sodium-Potassium eutectic (NaK) | Liquid at room temperature, common, not corrosive, non-toxic | Highly chemically reactive, high 14-hour induced radioactivity (it emits about 30,000x more radiation than water during operation and takes days rather than minutes to subside after shutdown) | EBR-1 |

| Sodium metal (Na) | Commercially available, cheap, non-toxic, non-corrosive | High 14-hour induced radioactivity, solid at room temperature, chemically reactive | Fermi-1, SRE, Hallam, EBR-2, SEFOR, FFTF, Phenix, SuperPhenix, BOR-60, BN-350, BN-600, BN800 |

| Lithium (Li-7) | Extremely good heat transfer, 5x smaller/lighter pumps than for Na (United States, 1961), Less chemically reactive | Requires isotopic enrichment of lithium, expensive, medium corrosive, medium toxic, generates tritium | LCRE (concept and/or classified) |

| Potassium | Cheap, non-corrosive, non-toxic | Chemically reactive | MPRE concept, SNAP-50 concept (secondary) |

| Lead | Cheap, no induced radiation, low chemical reactivity, keeps fast neutrons moving fast | Toxic, corrosive, heavy, hard to pump, melts at relatively high temperature (327 °C) | BREST |

| Bismuth | Keeps fast neutrons moving fast, low chemical reactivity, low toxicity | Expensive, corrosive, melts at relatively high temperature (271 °C), activates to hazardous & volatile Po-210 | |

| Lead-Bismuth eutectic | Melts at convenient low temperature (125 °C), keeps fast neutrons moving fast | More expensive than lead, toxic, corrosive, activates to hazardous & volatile Po-210, | USSR Alfa-class submarines, K-27 submarine |

| Cesium | Low corrosion, low toxicity | Expensive, chemically reactive |

Corrosion control due to impurities is key (Poplavsky et al., 2009).

Some more properties of liquid metals can be seen below

Mercury (Hg)

Mercury is a common liquid metal that has been commonly used for hundreds of years, e.g. in thermostats and thermometers. It is a liquid at room temperature, is not overly chemically reactive, and flows easily. It’s no surprise that it was used in the first liquid metal cooled reactor ever: Clementine. The heat transfer was unsatisfactory at Clementine, so various additives were put in the coolant. Because of this, mercury is no longer a popular reactor coolant.

In the Nuclear Space Program, a boiling mercury power cycle was developed, where vaporized mercury metal passed through an ultra-compact turbine. (See Mercury Rankine Program SNAP (YouTube))

If you let the mercury boil, then the heat transfer can actually be pretty good. (Bradfute et al., 1959)

Sodium-Potassium Eutectic (NaK)

When the mercury coolant used in Clementine proved inadequate from a heat transfer perspective, a eutectic (mixture) of sodium (Na) and potassium (K) metal was utilized next, in the Experimental Breeder Reactor I. Like mercury, NaK is a liquid at room temperature, avoiding the serious complications in cooling and thermal stresses that come from coolant phase changes. Unfortunately, NaK is highly chemically reactive, demanding careful handling and tight specifications related to leak-tightness and moisture content.

Sodium (Na)

Nuclear grade impurity levels and maintenance due to corrosion are essential (Latgé, 2017)

Lead (Pb)

Lead does not significantly activate under irradiation. This is a major advantage in both operation and in leak scenarios.

On the downside, lead is a dense and heavy metal. Pumping it requires large and powerful pumps that require significant power themselves. Pumping lead through large gravitational dimensions (e.g. tall things) is a challenge, so most lead-cooled cores are relatively short.

Bismuth (Bi)

Bismuth was first proposed as a coolant by Leo Szilard as a candidate coolant for the Hanford piles back in 1942. It is the original liquid metal reactor coolant idea.

It is far less common than lead and therefore more expensive.

Bismuth absorbs neutrons to activate to Polonium-210, which is an extremely radiotoxic pure-alpha emitter with a 138-day half-life. It can reach concentrations between 1–10 Ci/kg in normal reactor conditions (Buongiorno et al., 2004). Since alpha particles don’t penetrate pipes and the coolant system is sealed, it does not represent a hazard during normal operation, but rather is a concern during maintenance and leak cleanups when the primary coolant barrier fails. Po-210 is volatile and builds up in cover gas, which can leak through seals during operation. When the USSR operated lead-bismuth cooled Alpha-class submarines, they employed Po-210 cleanup systems.

Lead-Bismuth Eutectic (PbBi)

Pu-Bi eutectic is a mixture of Lead and Bismuth that exists in liquid form at lower temperature than either pure fluid.

Obviously, it has the Po-210 activation concerns described above as well.

Lithium metal (Li-7)

Lithium metal has an absurdly high heat capacity. This has led to its utilization in numerous extraordinary reactor concepts, such as the LCRE.

Lithium naturally contains 4.85% of the Lithium-6 isotope, the rest being Li-7. For in-reactor use, lithium must be isotopically enriched to very high purity of Lithium-7 for two related reasons:

- Lithium-6 is a very strong neutron absorber, which hurts the chain reaction

- For each neutron Lithium-6 absorbs, a tritium atom is generated. Because it’s so small, tritium is a highly mobile radionuclide that has a pesky habit of escaping even sealed metal boundaries into the environment.

Enriching lithium is a significant cost adder.

DEGREE OF FREEDOM ALERT

Note that the fact that you can choose the isotopic composition of each reactor material to specialize its nuclear properties to best suit your preferences further exacerbate the combinatorial complexity of reactor design. The isotopics of each coolant, moderator, structure, control, fuel, etc. can be adjusted continuously, thereby truly showing that the set of possible reactor designs is uncountably infinite.

Potassium (K)

Liquid metal potassium was proposed as the primary coolant and direct working fluid in the MPRE. Yes, you can make a liquid metal vapor turbine!

It was also planned as the secondary coolant in SNAP-50 and LCRE.

Heat Pipes

Heat pipes are a form of liquid metal coolant, where the liquid metal is in a vapor form inside a tube, which often also contains a wicking structure. Heat moves passively from a heat source connected to one end to a heat sink connected to the other. They are often found in consumer electronics such as laptops. They have no moving parts and are low maintenance.

On the downside, there are five operational limits to heat pipes that kick in at different geometries and operating conditions:

- The viscous limit (low temperatures) — the vapor pressure in the evaporator is insufficient to drive the vapor flow toward the condenser section.

- The sonic limit — choking in the vapor flow limiting the mass flow rate.

- The capillary limit – when capillary pressure is insufficient to balance the pressure drops along the heat pipe.

- The entrainment limit — when the vapor flow shears off the liquid at high-velocities, causing the wick to dry out.

- The boiling limit — when high temperature boiling causes the wick structure to dry out and block the liquid flow along the wick.

Practically, these limitations prevent heat pipes from being used on large or high power reactors. Still, they are great for high-cost fringe applications like remote power, where simplicity and reliability are at a premium.

Molten salt coolants

Molten salt can be used as a fuel or as a coolant. When put to work as a pure coolant, fuel-related constraints, such as how much uranium, thorium, or plutonium it can dissolve, fall away.

Non-nuclear systems use molten salts. Most notably, Concentrated Solar Power (CSP) plants often use nitrate salts to collect and move heat. Solar salt is a low-temperature eutectic, \(\text{60 NaNO}_3 - \text{40 KNO}_3\).

TIP

Many people mistakenly conflate molten salt and liquid sodium, probably because foods that are low in salt are for labeled “low sodium” instead of “low salt”. Liquid sodium is a shiny flowing metal that conducts electricity, like what the T-1000 is made of in Terminator 2. Molten salt is what you get if you heat up table salt in a super high-temperature oven. It’s melted salt. There is only one liquid sodium (elemental sodium) but there are thousands of salts that can be heated up and melted. In reactors, various fluoride and chloride salts are most common, but there are plenty more. We have a page on this.

Fluoride salt coolants

FLiBe is a common choice for salt-cooled reactors. It was identified in the aircraft reactor program as having appropriate properties as a coolant.

There are some economic challenges with FLiBe. The lithium generally has to be isotopically enriched in Li-7 to minimize parasitic neutron absorption and tritium production from the Li-6 isotope.

Futhermore, Beryllium is an industrial inhalation hazard. This is more of a concern when machining solid beryllium, and certainly can and is handled with appropriate precautions, but it’s certainly another cost adder.

Beryllium is also a somewhat rare material shrouded in fairly obnoxious secrecy and ITAR-related issues because of its use in components of nuclear weaponry.

As with other salt coolants, the melting temperature of FLiBe is pretty high. The tanks and pipes must have external electrical heaters to prevent thermal stresses from thermal expansion, and to maintain the coolant’s ability to flow and transfer heat.

Chloride salt coolants

Chloride salts could be used as direct reactor coolants, but as far as I’m aware there are no published concepts that use this. Reactor concepts fueled with a chloride salt fluid fuel are much more common.

Gaseous coolants

Blowing or circulating a gas through a nuclear chain reaction to carry the heat away is a primordial reactor design idea. The benefits include:

- High temperature capability — Since gasses have already boiled, they are are the most common coolants of choice for reactors that aim to operate at very high temperatures (700 °C and beyond).

- Good thermal efficiency — High temperatures allow improved thermal efficiency

- Access to better power cycles — High temperatures allow direct or indirect use of Brayton-cycle power conversion (i.e. gas turbines instead of steam turbines). These can be more compact and efficient. They can also maintain efficiency over a wide variety of power fractions, crucial for operating economically in marine propulsion or in other load-following modes.

On the downside:

- Low power density — Since gas can depressurize rapidly, gas-cooled reactors must operate at low power density. Otherwise, the decay/afterglow heat rate would be too high and the fission products contained in fuel could escape. This ends up making gas-cooled reactors very large per unit power.

- High pumping power — gas cooling requires much higher pumping power per heat transfer than other coolant. It’s not uncommon for the gas blowers to use up 10% of the total reactor power. This offsets the high thermal efficiency to a degree.

- Leaks — Gasses have low density. To pick up and transfer appreciable heat, they are almost always used in a high pressure arrangement. High pressure leads to challenges in leaking and requires pipes and structures strong enough to contain it.

Any gas can work, but several have been used and seriously considered.

Table 2. Pros and cons, and a W'/q heat transfer metric for several common gaseous reactor coolants normalized to H at 80 °F, from (El-Wakil, 1962)

| Gas Coolant | W'/q @ 600 °F | Pros | Cons | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air | 11.9 | Common, cheap | Poor heat transfer, corrosive due to oxygen, activates to radioactive Ar-41, N-16, and C-14 | CP-1, CP-2, CP-3, X-10, Windscale, HTREs |

| Nitrogen | 11.9 | Common, cheap | Poor heat transfer, activates to C-14, embrittles materials via nitriding | GCRE, ML-1 |

| Steam | 2.65 | Common, cheap | Corrosive, activates to Ar-41 and N-16 | Steam cooled fast reactor concepts |

| Carbon dioxide | 4.84 | Common, cheap | Radioactive C-14 builds up in loop, N-16 present during operation | Calder Hall, UNGG, Magnox, AGR, EL4, Lucens |

| Helium | 5.1 | Good heat transfer, chemically inert, no activation | Uncommon, expensive, difficult to contain | Dragon, Peach Bottom, AVR, THTR, UHTREX, Ft. St. Vrain, HTTR, HTR-10, HTR-PM |

| Hydrogen | 0.91 | Good heat transfer, common, cheap | Explosive, high neutron capture, difficult to contain | NERVA |

Neon has been investigated as an alternate to helium, since it has good nuclear properties, but it is much harder to pump effectively (Easby, 1976). Argon is more readily available (it’s 0.9% of air), but generates the hazardous airborne isotope, Ar-41, under neutron irradiation. Methane and ammonia could be good coolants given sufficient chemical stability in reactor conditions (El-Wakil, 1962).

Organic coolants

(Coming soon, but until then, watch this OMRE film)

References

- Fox, E. C., Fuller, L. C., & Silverman, M. D. (1977). Assessment of High Temperature Nuclear Energy Storage Systems for the Production of Intermediate and Peak-Load Electric Power (No. ORNL/TM-5821; Issue ORNL/TM-5821). Oak Ridge National Lab. (ORNL), Oak Ridge, TN (United States). https://www.osti.gov/biblio/7213843

- Hogerton, J. (1964). Nuclear Reactors. US Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). https://www.osti.gov/biblio/1132519

- U.S. Atomic Energy Commission. (1963). USAEC Power-Reactor Development Programs. United States Atomic Energy Commission, Division of Technical Information. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001627626

- El-Wakil, M. M. (1962). Nuclear Power Engineering. McGraw-Hill. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001619587

- United States. (1961). AEC Authorizing Legislation Fiscal Year 1961: Hearings before the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy, Congress of the United States, Eighty-seventh Congress, First Session One. U.S. G.P.O. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/012403651

- Poplavsky, V. M., Kozlov, F. A., Orlov, Y. I., Sorokin, A. P., Korolkov, A. S., & Shtynda, Y. Y. (2009, July). Liquid Metal Coolants Technology for Fast Reactors. FR09: International Conference on Fast Reactors and Related Fuel Cycles: Challenges and Opportunities, Kyoto (Japan), 7-11 Dec 2009; https://inis.iaea.org/collection/NCLCollectionStore/_Public/41/070/41070002.pdf?r=1

- Alder, K. F. (1958). Liquid Metal Fuel Reactors. Proceedings, 2, 27. https://www.osti.gov/biblio/4311480

- Bradfute, J. O., Battles, D. W., Clark, G. S., Corridan, R. E., Gellenbeck, E. T., Kavanagh, D. L., Mash, D. R., Romie, F. E., & Whitlock, R. H. (1959). AN EVALUATION OF MERCURY COOLED BREEDER REACTORS (No. ATL-A-102; Issue ATL-A-102). Advanced Technology Labs. Div. of American-Standard, Mountain View, Calif. https://doi.org/10.2172/4170077

- Latgé, C. (2017, July). Sodium Coolant: Activation, Species Production Coolant Processing and Handling Procedures. 1ST IAEA WORKSHOP ON CHALLENGES FOR COOLANTS IN FAST NEUTRON SPECTRUM SYSTEMS. https://nucleus.iaea.org/sites/fusionportal/Shared%20Documents/Workshop%20Coolants/Presentations/5.07/Latge.pdf

- Buongiorno, J., Loewen, E. P., Czerwinski, K., & Larson, C. (2004). Studies of Polonium Removal from Molten Lead-Bismuth for Lead-Alloy-Cooled Reactor Applications. Nuclear Technology, 147(3), 406–417. https://doi.org/10.13182/NT04-A3539

- Easby, J. P. (1976). A Comparison of Neon, Neon/Helium Mixtures and Helium as Reactor Coolants. Atomkernenergie, 27(4), 235–238. http://inis.iaea.org/search/search.aspx?orig_q=RN:07263485

Also, see the Coolants chapter in (Rodden, 1964) for detailed reference information about coolants.