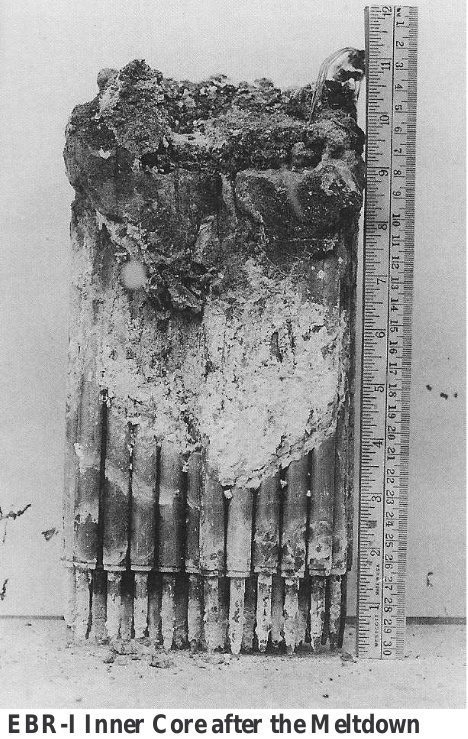

The EBR-1 core melt

By Dr. Nick Touran, Ph.D., P.E., 2022-09-26, Reading time: 3 minutes

What happened?

EBR-1 had accomplished its primary mission of proving that breeder reactors could indeed breed more fissle material than they consume. Later, on November 29th, 1955, an experiment was performed to try to better understand some unexpected reactivity feedback that had previously been observed at low power/flow ratios. During the experiment, the reactor increased in power faster than expected. A shutdown was ordered but the operator pressed the “slow shutdown” button (which slowly moved the reflector) rather than the “fast shutdown” button (which quickly dropped the reflector). The core melted, radiation alarms went off, blockage was noted, and the building was evacuated. Later, the core was rebuilt and the research into core mechanical feedback was completed so the reactor could retire with honor.

Lessons

Don’t rely on human operators to actuate shutdown when it’s necessary

This event is an early example later, followed by more serious events like #chernobyl, of disabling automatic shutdown systems and relying on humans during a test. Though an automatic scram signal was still in place, it wasn’t set conservatively enough to avoid core melt. A scram signal based on low reactor period had been disabled.

Don’t be surprised by sensors that are not working

Some thermocouples were registering coolant temperatures instead of fuel slug temperatures. This should have been noticed earlier via some kind of redundancy or other inference.

Use auto-scaling instruments

It’s unfortunate that the power excursion went “off scale” for a while on the instrumentation. If it could have auto-scaled and stayed on the paper, we would have had better data from which we could understand core damage accidents better at an earlier time.

Legacy

Besides the lessons above, the EBR-1 experiments led to some fundamental design changes for fast reactor mechanical core restraint. In the end the determined that it was a combination of two competing neutronic/mechanical feedbacks that cause the situation:

-

The upper support plate that held the pins would heat up on the bottom more #than the top, causing it to “cup” downward and spread the pins out, introducing #negative reactivity with negative feedback.

-

If the fuel heated up before the upper support plate, their thermal expansion #would cause them to squeeze into each other, introducing positive reactivity #with positive feedback.

After EBR-1, reactor designs tended to leave their pins within assemblies unrestrained at the top and pinned at the bottom so that neither of these effects will happen.

References and more info

-

EBR-I Core Disassembly after Meltdown – Video from the event

This page is a part of our Safety Minute collection. You can edit it or add more on GitHub.